I want to talk about a common misconception – or perhaps simply “mis-emphasis” – that I see frequently in popular entertainment and media: The Butterfly Effect.

The familiar statement of this concept derives from a 1972 lecture by Edward Lorenz who first described the effect mathematically: “…a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could set off a tornado in Texas.” This concept has now permeated popular culture in the form: “The future is entirely non-deterministic.” In addition, popular culture and media also generally treat this latter formulation as synonymous with “chaotic.”

However, both of these characterizations are incorrect, although it is easy to see how this happened. Lorenz’s math was the final nail in the Poincaré coffin of Laplace-like determinism and his clean statement of future outcomes being unpredictable beyond certain points in time (even if initial conditions are known) was staggeringly significant.

But there are two extremely important distinctions which are often missed in The Butterfly Effect and have led to the popular misconceptions in the wider culture.

The first is that “chaotic” is the same as “random.” This is not the case. To use the analogy, even though the butterfly flapping its wings might (even Lorenz thought he may have misstated the possible impact of butterflies) lead to a tornado in Texas, it will not lead to, say, a man buying a hot dog in Munich or a baby being born one minute later in Mumbai.

To understand why this is the case we need to look at the second common misunderstanding: “the future is entirely non-deterministic.”

The best expression of this is from an MIT Tech Review article:

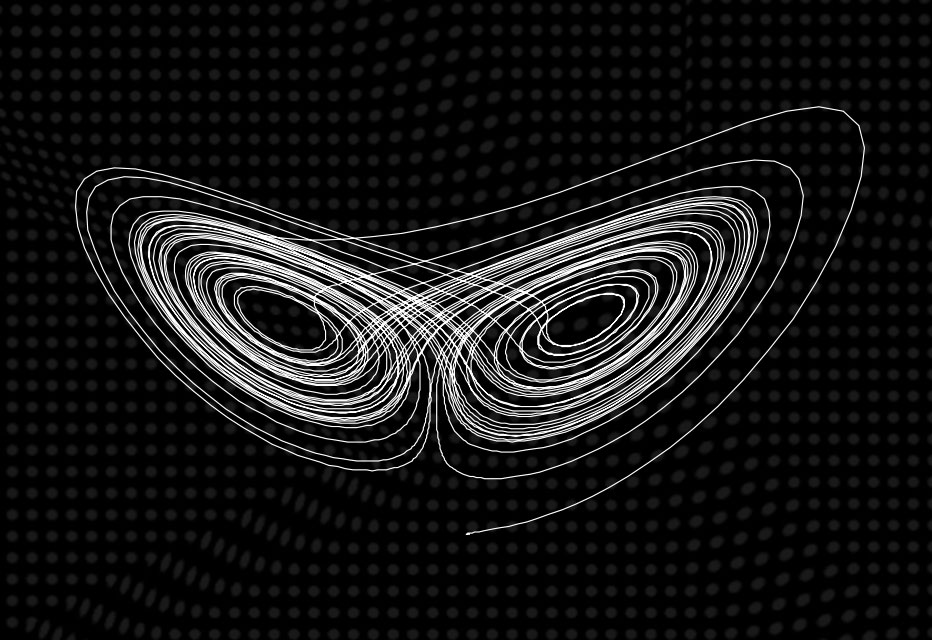

“Yet chaos is not randomness. One way that he demonstrated this was through the equations representing the motion of a gas. When he plotted their solutions on a graph, the result—a pair of linked oval-like figures—vaguely resembled a butterfly. Known as a “Lorenz attractor,” the shape illustrated the point that almost all chaotic phenomena can vary only within limits.”

A version of this statement is always made in articles and posts about Lorenz’s math, but somehow the importance of it never seems to make it out into the general conception of The Butterfly Effect.

The key here is the statement “…can vary only within limits” and it is this which seems to be the core of the misunderstanding of the effect. Can we predict precisely what the weather will be like in two weeks’ time? No. Can we predict it will not be 45 degrees Celsius in Vienna on January 1st, 2024? Yes.

Could the tornado itself have a knock-on effect that then causes another effect which causes another effect which eventually causes a man to buy a hot dog in Munich? Perhaps. So this is not to say that every event in the universe is not distantly connected to earlier events which no one could have predicted would be part of a chain. But the point is that EACH event has an ENVELOPE of possible results and thus there ARE events that can NEVER be caused by a SPECIFIC “wing flap.”

Taken together, does this mean our lives and the universe are deterministic? No. Does it mean they are completely random and unpredictable? Also no.

Perhaps “chaos theory” was a poorly chosen name? I generally wish physicists and mathematicians would consult with poets before naming things, but this is a particularly good example of a naming convention causing a lot of misunderstanding. Mathematician James A. Yorke coined the term “chaos theory” in 1975, and, to be fair, I do understand what he meant.

The technical definition of chaos is “total disorder or confusion” and I think Yorke thought “ah, ‘confusion,’ fair enough!” But, unfortunately, (and I’m not sure James Gleick really helped the situation), we now understand ‘chaotic’ to mean “totally random” at this point in time.

The Butterfly Effect is neither “total” nor “random” and it would be interesting to see a deeper, more nuanced understanding of its metaphysical implications for the meaning of our existence enter popular culture. This is especially at a time when the concept that the circumstances of a person’s birth determine the bounds of their future is so central to our general discourse.