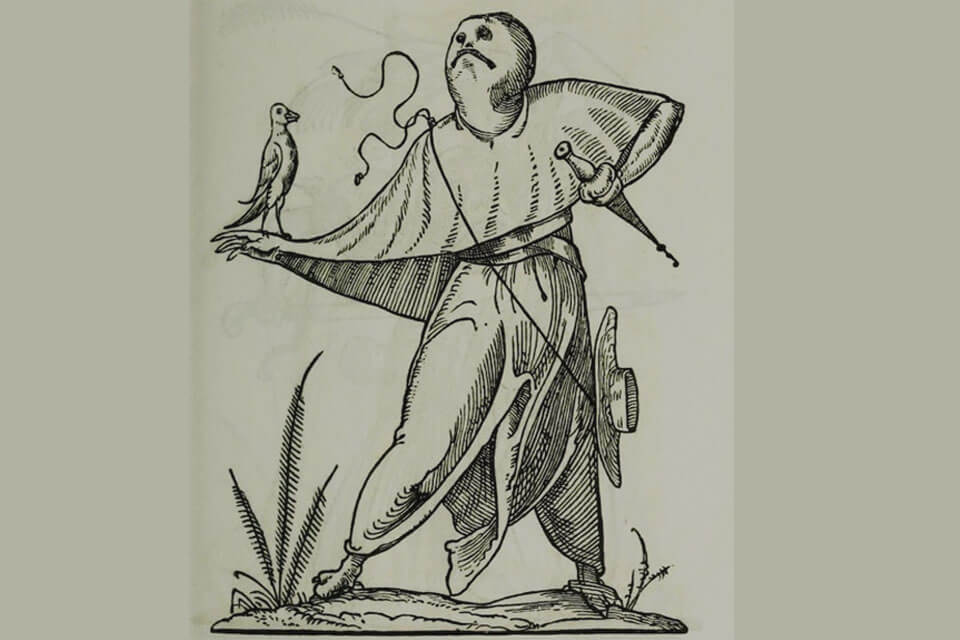

In 1565, shortly after the publication of the last volume of Rabelais’ “Life of Gargantua and Pantagruel,” a book was published by Richard Breton containing 120 engravings of fantastic figures. The book claimed to be associated with Rabelais but was actually the work of François Desprez. The full book is archived here and is absolutely worth a look.

The book was titled, “Les Songes drolatiques de Pantagruel,” (“The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel”), and people have been trying to translate the meaning of the word “drolatique” into English ever since. It means something like ironic and satirical simultaneously and is, most likely, related to the word “droll” in English which, in turn, may come from the Middle Dutch word for “goblin.”

This etymology is very apt for The Drolatic Dreams since it is a book populated by goblins. (Maybe the publisher knew more of this derivation than we do today?) But not just any goblins; goblins that, for some reason, demand deep contemplation.

The book has been the focus of much conversation, analysis, and debate over the centuries, as well as inspiring the likes of Dali to riff on its drawings. And it makes me ask the question: what makes something a meditative focus? By that, I mean, why do some images draw us in and begin a journey while some do not?

There is a theory that the Major Arcana of the Tarot were created as meditative foci for Gnosticism. And these images share a certain quality with those of the Drolatic Dreams. Obviously, some of the Major Arcana, like The Tower, contain a moment of frozen action. Such moments demand a cause and effect to be drawn in our minds: a before and an after which naturally lend themselves to a narrative which can become a meditative journey if we allow our consciousness to roam free from that beginning.

But many do not. And the images in the Drolatic Dreams are of this more static nature. They are “simply” portraits. And yet there is something about them that draws us in and forces us to undertake a journey with them.

When we begin this process, I think, it is a quest, on our part, for meaning. We want to discern the hidden semantics behind them, solve their puzzle, identify the specific king or queen or priest or lawyer they seem to be ridiculing. But, after a time, we let that go and the images take us on their own voyages.

And perhaps this is the deeper answer. Maybe it is images that serve as a bridge between the conscious and unconscious which are able to provoke this kind of deeper response. If an image has many details but the details are of an easily identifiable nature, we spend time contemplating them, but then dismiss them when we decide we have their “answer.” A portrait, for example, of a woman with a pen in hand and an open book with handwriting on its otherwise blank pages makes us first ask, “What is that book?” but then answer, “Probably her diary or journal.” And we are done. The journey begins but ends very quickly.

When an image is highly, but concretely, representational, we try to identify its elements, but then end our interaction with the image when we have our answers.

Likewise, when an image is highly abstract, it is harder for the journey to begin. We may, possibly, make the leap directly to some surprising feeling or thought, but it is often harder to do so and I think this may be why so little abstract art has truly broad appeal.

But when the image is in the Goldilocks zone between representation and abstraction, it allows us to “slip into the waters” of our unconscious and realize how endless they can be. Surrealism and the works of Bosch (bookending The Drolatic Dreams in a way) are, of course, two of the most clear examples of this concept and were arguably intended in this way. (There is, for example, an exhibit about the relationship between Freud and Dali I would highly recommend if you happen to in Vienna right now).

But such an effect can happen with any image. When it contains just the right balance between the known and the unknown, it too can become a drolatic dream. They provoke our quest for life’s meaning, a meaning which can never really be found, but for which natural selection has wired our brains to search by favoring those ancestors who could unlock the mysteries of the weather and the passage of the sun.